India’s building landscape is rising vertically and densifying rapidly, placing unprecedented demands on fire protection systems. Compliance alone cannot guarantee safety; what matters is how these systems behave under real conditions, when water, air, power, people, and pressure interact simultaneously. This article examines fire protection not as a checklist of installations but as an engineering ecosystem that requires predictable hydraulics, reliable pressurisation, integrated controls, and dynamic commissioning.

It explores how high-rise towers, hospitals, malls, hotels, and data centres must shift from equipment-driven design to performance-driven engineering rooted in India’s unique climatic, operational, and infrastructural realities. The goal is clear: a future where fire protection systems are not just installed to meet codes, but engineered to protect lives with consistency and confidence.

Where Fire Safety Actually Begins

Fire safety in India often begins with drawings and ends with checklists. Yet buildings themselves do not react to fire in a checklist format. They react through physics—pressure differentials, airflow turbulence, heat rise, smoke migration, water behaviour, pump sequencing, door performance, and human movement. This is where the engineer’s perspective becomes essential. Fire protection must be understood as a living system, not a fixed installation.

If systems are designed only for ideal conditions, they will struggle when the real building behaves differently: when doors stay open longer than expected, when wind speeds fluctuate across floors, when water friction losses increase with pipe aging, or when smoke takes a path no drawing anticipated. India’s buildings need a lens that moves beyond the installation mindset and embraces engineering behaviour.

Hydraulics: The Lifeline of Water-Based Fire Protection

Water-based firefighting systems succeed or fail on the strength of their hydraulics. In high-rise buildings, the vertical distance alone introduces significant challenges. Every metre of height adds static pressure; every bend, tee, or scaling inside pipes adds friction; every assumption about water quality affects valve performance over time. In many Indian cities, water quality accelerates mineral deposition and internal corrosion. A pipe designed with a theoretical Hazen-Williams coefficient of 120 can behave like a pipe with a coefficient closer to 100 within a few years. This shift translates into major friction losses over long vertical runs.

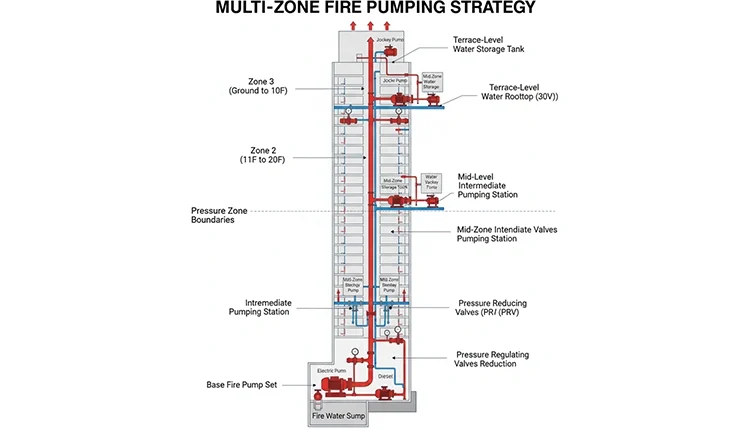

When friction loss combines with static head, the uppermost hydrants or sprinklers may struggle to maintain the minimum residual pressure of 3.5 kg/cm² under true flow conditions. For very tall buildings, expecting a single pump at the base to handle extreme static pressures, dynamic losses, and varied demand profiles is unrealistic. Pressure zoning and intermediate pumping floors are not design luxuries; they are engineering necessities.

Air and Smoke: The Real Determinants of Life Safety

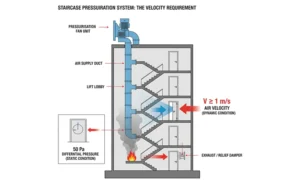

Firefighting begins with water, but human survival depends on air. Smoke is the real threat in most building fires, and controlling it requires an engineering mindset. Pressurisation systems for staircases and lift lobbies are usually designed around static pressure requirements. Yet evacuation is a dynamic process. Doors remain open as people move, pressure collapses, and smoke begins to chase that pressure drop.

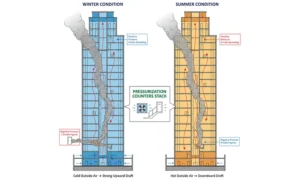

The requirement to maintain an air velocity of at least 1 m/s across an open door is not a theoretical guideline—it is the difference between a corridor filling with smoke and a corridor remaining tenable for evacuation. Tall buildings introduce even more variables. Stack effect can intensify or reverse airflow paths depending on external temperature, internal air conditioning loads, or wind pressure across façades. A well-designed pressurisation system must adjust automatically rather than operate at fixed speeds.

Integration: Making All Systems Speak the Same Language

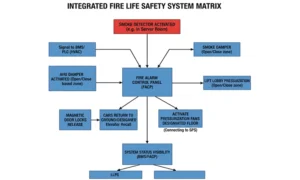

In modern Indian buildings, multiple systems converge during a fire—fire alarm panels, BMS, AHUs, fire pumps, motorised dampers, access controls, elevator systems, and emergency power networks. If these systems do not communicate seamlessly, response time increases, smoke transfer accelerates, and evacuation efficiency drops. True integration begins with a unified control philosophy where each action—detector activation, pump start, damper movement, AHU shutdown, elevator recall—is part of a single, predictable chain.

A coordinated system relies on accurate programming, clear communication protocols, redundancy in wiring, and real commissioning under simulated conditions.

Smoke Management: Designing for Real Behaviour, Not Ideal Assumptions

The movement of smoke defines whether a building remains survivable. Smoke does not respect architectural intent; it follows pressure, heat, and openings. Therefore, smoke management must be engineered around how real fires behave. High-rise residential buildings require stable pressurisation despite uneven occupant behaviour. Commercial towers rely heavily on fast AHU shutdown and plenum isolation to stop smoke from being distributed through return air paths.

Hotels and malls carry complex fuel loads and variable compartmentation, requiring engineered smoke reservoirs, extract strategies, and corridor protection. Hospitals present entirely different challenges—patients cannot always be moved, life-support equipment cannot be shut down, and smoke must be contained long enough for staff to execute phased evacuation.

Commissioning: When Systems Prove What They Can Actually Do

A fire protection system is only as reliable as its commissioning. Designing, installing, and certifying a system is not enough. Commissioning is where the building demonstrates whether theory translates into performance. True commissioning must evaluate the system under dynamic conditions, not controlled demonstrations. Water networks must be tested at full pump flow while measuring real residual pressure at the highest point of the building.

Pressurisation systems must be tested with doors opened and closed, with lobbies occupied, and during simulated fire scenarios. Integration must be validated by initiating alarms from different parts of the building and observing the full sequence of system responses.

Lifecycle Performance: Designing for the Next Thirty Years

Fire protection systems age. Pipes scale, pumps lose efficiency, dampers accumulate dust, seals degrade, sensors drift, and fit-outs evolve. A system that performed flawlessly on day one may behave differently five years later. This is why fire protection must be viewed through a lifecycle engineering lens. Water quality must be monitored to understand how pipe friction is evolving. PRVs must be checked under flow conditions. Pressurisation fans require periodic tuning. Seals around shafts and doors must be inspected regularly to prevent unseen leakage paths.

Conclusion: Engineering Safety That Endures

India’s vertical growth demands a new understanding of fire protection—one rooted in behaviour, not just compliance. Systems protect buildings when hydraulics, airflow, integration, and power systems behave predictably and cohesively under stress. Fire safety becomes meaningful when designers anticipate real pressure losses at height, when pressurisation is tuned for realistic evacuation behaviour, and when commissioning proves performance rather than merely installation.

The buildings India is constructing today will stand for decades. Their fire systems must be engineered to operate reliably far into the future, despite changes in occupancy, environment, and layout. A practical engineering lens ensures that fire protection evolves into a coordinated, resilient life-safety ecosystem capable of protecting every occupant, every time.

Madhava Narasimha Murthy Nedunuri is a senior MEP leader with two decades of experience delivering complex high-rise, township, mall, hospital, hotel, and data-center projects across India. He began his career with engineering roles in IL&FS, Shapoorji Pallonji, HCC, and Bhartiya Urban (formerly Urbanac), progressing into strategic project leadership positions where he shaped design standards, execution quality, and safety culture. His work blends deep technical understanding with a systems-thinking approach to MEP integration, hydraulic performance, fire engineering, and sustainability. Known for his clarity in engineering logic and his commitment to mentoring teams, he continues to contribute to industry conversations through technical writing, thought leadership, and applied field insights.