Recently, I was having a discussion with a senior safety manager regarding “near-miss” reporting. He was fairly adamant that the people submitting the reports should have to put their name on it. I was advocating that if they wanted more, they should make it anonymous. He said that since they had made it easier to report via mobile technology that they had seen a 600–700% increase in near-misses, and that he was confident that they were getting all of them or almost all of them reported. I realized this question went beyond the seemingly simple question about anonymous near miss reports. It has ramifications for culture and climate, leadership, and personal skills development.

As we passed by a few forklifts parked beside each other I asked him to stop. Then I asked if he noticed all the black marks and dings on the forklifts (there would have been dozens on each one). “Did you buy them that way?” I asked.

“Well no,” was the answer.

“Do you have a near-miss report for every one of those marks?”

“Well no,” was the answer again.

“If it was a person, instead of a pole, guard rail or piece of equipment that was hit, could it have been serious?” I asked.

“Yes,” was the answer. But the tone of his voice had changed considerably.

He knew that I knew they’d had a serious injury with a big piece of mobile equipment and a contractor just before I got there. “Why do you think they didn’t fill out a report for every one of those incidents?” I asked.

There was a pause, and then he said, “I don’t know, but we do get some.”

So then I asked him another question: “If you reported every incident, every time you even touched something unintentionally with the fork truck, or a pedestrian had to move quickly to get out of the way—but the other drivers didn’t—would you eventually get blamed for not being a good driver?” Again, there was a pause. But it was longer this time.

“Yes…” I could tell that he was getting uncomfortable and it was time for me to change the tone.

“Don’t worry,” I said lightly-heartedly, “everyones’ forklifts look like that, even at the places where they make them, and they don’t have near-miss reports for all of them either.” I knew I had made my point about making the reports anonymous so I didn’t say anything about that. Instead I just asked, “For the reports you do get, what do they say? Are there usually extenuating circumstances, like the weather or something?”

“Yeah, (big sigh), people never admit it’s their fault.”

Then, just to make sure things stayed light-hearted I said, “This has probably been one of my favourite questions over the years, but have you noticed that the quality of your excuses has improved tremendously since you were a little kid?” He just laughed, and I could tell most, if not all of the tension had been released. And almost everybody does laugh when I ask that question. But seriously, where did we learn those skills? It’s not like we were born with them. So the “blame game”, and it is a bit like a game, started way before we ever got a job. And the reason I think “blame game” is appropriate is that if your excuse worked, it’s like you won, and if it didn’t it’s like you lost or rolled “snake eyes” with the dice. As a result, only the excuses that worked were ever used again and the excuses that didn’t—weren’t.

In certain cultures, admitting fault or that you made a mistake is like “losing face”. It is deeply ingrained. When I was first in Asia, I realized that I would need to do more than just introduce the elephant in the living room. That wouldn’t (figuratively speaking), be enough, I would have to grab the bull by the horns. So I started the session by asking these questions: “If someone told you that they didn’t make any mistakes, would you believe them?” They all shook their heads or said, “No.” Then I said, “You would know they were pretending.” This time they all said or nodded “Yes.” Then I asked, “So why do people pretend they don’t make any mistakes, when they know that everyone knows they are pretending?” Now they all looked around at each other as if to say, “I think he’s talking to us” and thankfully, most of them started to laugh. The laugh gave me the go ahead to continue with the serious point: “You realize,” I said ”that no matter how good you get with the pretending or the excuses, it will never prevent the next one.” Now, they all nodded, but it was a very serious nod. “And the next one could be worse or a lot worse.” I paused for a second to let that sink in, and then I said, “Imagine how much better off we would all be if the same effort was put into analyzing and improving instead of pretending or making excuses and trying to cover up our mistakes?” Again, they all nodded in agreement, so I said, “Let’s move on…”

Even in other parts of the world, where it’s not as extreme, the point of the last anecdote was to illustrate or to help you as a manager or safety professional realize the depth of the problem, or the difficulty you will be facing if you are trying to create a truly blame-free culture, where people learn how to analyze every mistake instead to getting better at the diminishing and deflecting or the rationalizations. In short, it’s not going to be easy. Even if you believe in it, we all know that not everyone does.

Sometimes people will be sympathetic or even empathetic and say, “Don’t worry, I’ve made that mistake before” or “I’ve made that mistake many times before,” but (alas) that’s not always going to be the case. And somewhat ironically, most people prefer to “stay on the safe side” and offer a good excuse or to say nothing, which is why we don’t get a near-miss report for all the black marks and dings on the forklifts. Whereas the truth, if we really wanted to stay on the “safe side”, would be to report it, and see if there might be something that can be done to change the system, environment or context.

Granted, there might not always be a practical solution or a cost-effective option (we can’t really “bubble-pack” the world). But I think most people can accept the truth about this next statement: It’s impossible to do anything in terms of changing the system, environment, etc. if we don’t know about it in the first place. However, if there isn’t a practical, cost-effective option, then we have to give people a different framework to analyze the mistake and be able to learn from it, instead of telling them or having them tell themselves that they have to be more careful/pay more attention in the future or at least come up with a better excuse next time. So how do you do it? What are the steps?

First, we need to accept that it’s going to take some time. Cultures don’t change overnight and ingrained behaviors don’t either. The good news is leaders can develop skills to influence elements of safety climate that, if done consistently, will in time have a positive effect on culture. In this example, creating a climate where leaders do not default to blaming people will foster trust and engagement that will lead to an increase in near-miss reporting and ultimately more sustainable solutions. Leaders who build trust and engagement by taking a responsive vs. reactive approach to problem solving are more likely to influence people to work on safety skills that will develop into habits.

Second, we need people to realize that everyone makes a lot of mistakes–every day. If you ask people how many mistakes do you make? The answer you get from everybody is, “too many”. But how many is it really? What do the experts or neuroscientists say? Answer: around 80 a day. Ok, next question, what causes the majority of these errors: ignorance or human factors like rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency? Answer: over 95% are caused by human factors. Ok, now think about how many times you see human factors on your incident reports? How many times do you hear, “I just wasn’t thinking about what I was doing and the risk of what I was doing when I got hurt”? Answer: probably not a lot (if ever). And yet, when you ask people if they can tell you a time they’ve been hurt when they were thinking about what they were doing and the risk of what they were doing in the moment they got hurt (not including sports) you won’t likely get one example…

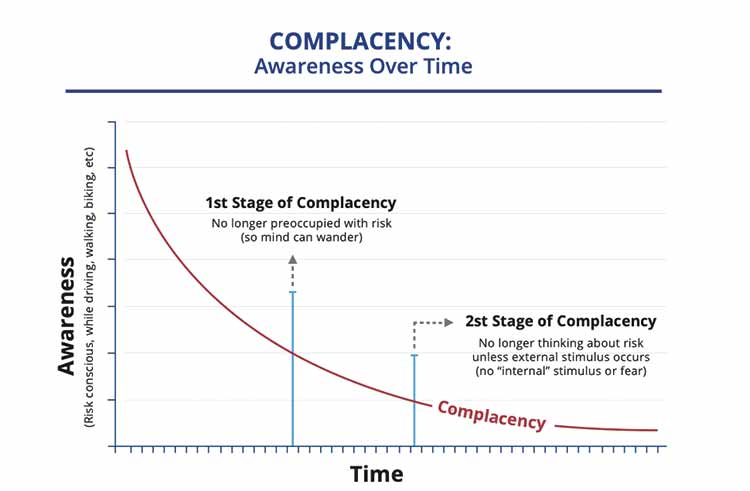

This gives you an idea of how important paying attention is when it comes to preventing injuries and incidents. For most of us, if we were paying attention and thinking about risk, we didn’t get hurt, period. However, it’s not really possible to pay attention once you become competent or once the fear of the skill is no longer preoccupying (see Figure #1 – Complacency Continuum, first stage). Furthermore, once you have passed the first stage, everyone becomes very susceptible to rushing, frustration and fatigue because you will likely be thinking about why you are rushing, who or what you are frustrated with, or when you can take a break or get some rest.

Now, once people understand how these human factors affect our ability to focus on the task at hand, it starts to become much easier to accept the likelihood of errors and mistakes, even if you or they are competent or very competent. And now, instead of doing something that is totally useless like “re-instructing” or “re-indoctrinating” a competent worker (so you can fill in the last column on the incident report), you can talk about the states or human factors that caused or contributed to the error. However, this does not mean you should say don’t rush or don’t be frustrated and imply that they should “know better”. And the same is true for fatigue. First, we need to look at the system and see if somehow we are “institutionalizing” the state, like the way they make doctors work incredibly long hours when they are interns at a hospital or the way incentive systems for production bonuses are structured at some companies. There will be enough rushing, frustration and fatigue–in life. We don’t need to fan the flames.

Next, we need to teach the employees critical error reduction techniques like self-triggering on the active states: the ones you can feel in the moment (rushing, frustration and fatigue), and then teach them the techniques they will need to either “fight” or “compensate“ for complacency. To fight complacency you can look for state to error risk patterns, and to compensate for complacency people can work on their safety-related or performance-related habits, like leaving a safe following distance when driving. So that when your mind does go off task you have at least compensated for it by giving yourself more time to react. Same thing for getting in the habit of holding the handrail or wearing a seat belt, double-checking important items, etc.

Finally, you need to make sure that they can analyze the close calls or near-misses themselves. Maybe they could report it every time they hit something with a fork truck. But it’s not really practical to expect a report every time someone loses balance, drops their keys/phone or turns without looking first and bumps into something. But they could do the analysis for themselves: First they need to ask what states were involved. Then they need to know what critical error reduction techniques or what combination of techniques they could use in the future. And perhaps most importantly, that excuses or rationalizations won’t ever prevent the next one, and that we have all been victims (to a certain extent) of the blame game when it comes to preventing human error.

Afterward:

I started this article by saying I advocated anonymous reporting. To be clear, organizations with advanced safety cultures discuss this less and less. A culture where every person is willing to put their name on a near-miss report is an ideal, and an ideal worth striving for. Along the path to this ideal we will benefit greatly from encouraging leaders to share personal stories whether from work or outside of work where they made a mistake due to human factors or a combination of them. This will help to develop a no-blame climate and demonstrate the need for teaching everybody individual skills that can be used to reduce the number and negative impact of the inevitable mistakes we make every day. These practical steps can also have a profound positive impact on an organization’s culture.

For more information,

www.asia.safestart.com