Safety in High-Density Electrical Systems: The Hidden Risks of AI, EV, and Non-Linear Loads in Indian Buildings

Electrical systems in Indian buildings are undergoing a fundamental transformation that is not yet fully reflected in prevailing design practices or safety evaluations. The rapid adoption of AI-driven computing, electric vehicle charging infrastructure, UPS-backed digital loads, variable frequency drives, and power-electronic equipment has shifted electrical demand from predictable, linear behaviour to dense, dynamic, and highly non-linear operating conditions. While installed capacities have increased to accommodate rising connected loads, most electrical designs continue to rely on steady-state assumptions that no longer represent how systems actually behave in service.

This article examines how modern load profiles introduce hidden and often underestimated safety risks within building electrical infrastructure. These risks include harmonic-induced heating in conductors and transformers, neutral overloading in vertical risers, thermal stress in enclosed bus ducts, instability during DG–UPS power transitions, protection miscoordination under distorted waveforms, and degradation of earthing performance under high-frequency currents. Many of these failure modes do not result in immediate outages or visible alarms, allowing unsafe conditions to persist unnoticed until insulation failure, equipment damage, or fire occurs.

Rather than focusing solely on capacity adequacy, the article argues for a shift toward behaviour-based electrical engineering. It highlights the need to evaluate how electrical systems respond to waveform distortion, thermal accumulation, load coincidence, and transient operating conditions throughout their lifecycle. Practical engineering approaches are presented that emphasise realistic load profiling, harmonic assessment, thermal derating, system segregation, dynamic commissioning, and periodic performance validation. These strategies are discussed in the context of Indian building typologies and operational constraints, offering designers and operators a structured pathway to improve electrical safety as buildings adapt to increasingly complex and power-intensive technologies.

The Quiet Transformation of Electrical Risk

For decades, electrical safety in buildings was closely linked to installed capacity. If transformers were adequately sized, cables selected correctly, and protection devices coordinated as per code, systems were considered safe. Load growth was gradual, predictable, and largely linear. That assumption is no longer valid, yet it continues to influence many design decisions across residential, commercial, and mixed-use developments.

Modern buildings now host AI servers operating continuously at high utilisation, EV chargers delivering pulsed high-current demand, UPS systems rectifying and inverting power at scale, HVAC systems driven by variable frequency drives, and lighting dominated by switched-mode power supplies. These loads do not merely increase demand; they fundamentally alter current behaviour. Electrical networks now experience sharper peaks, distorted waveforms, and simultaneous operation of multiple non-linear loads across floors and zones.

What makes this transformation particularly dangerous is that traditional indicators of stress often remain within acceptable limits. Breakers may not trip, transformers may appear lightly loaded in kVA terms, and voltage levels may remain stable. Meanwhile, conductors heat progressively, insulation ages faster than expected, neutral currents rise beyond design intent, and protective devices operate closer to their limits. Electrical risk has shifted from being obvious and capacity-driven to being subtle, behavioural, and cumulative, demanding a more nuanced and technically grounded engineering response.

From Linear Loads to Power-Electronic Dominance

Traditional electrical systems were designed around loads that followed the voltage waveform closely. Motors, heaters, incandescent lighting, and conventional induction equipment drew current proportionally and predictably. Harmonic content was low, neutral currents were modest, and thermal behaviour could be estimated with reasonable accuracy using nameplate ratings, diversity factors, and demand calculations. Protection systems, cable sizing, and transformer selection were all developed around these assumptions, and for decades they held true.

Modern electrical loads behave fundamentally differently. AI servers and data processing equipment draw current in narrow, high-amplitude pulses with elevated crest factors. UPS rectifiers reshape current aggressively, often producing significant harmonic distortion even when operating below rated capacity. EV chargers combine high power density with intermittent and coincident usage patterns that defeat traditional diversity assumptions. Variable frequency drives continuously modulate voltage and frequency, introducing harmonics across a wide spectrum that varies with operating speed and torque. LED drivers and SMPS-based equipment inject high-frequency switching components that propagate throughout the electrical network.

The consequence is an electrical system where apparent stability masks real stress. RMS current increases without corresponding increases in useful power. Peak currents place additional strain on conductors, terminations, and protective devices. Neutral conductors experience loading conditions never envisaged in earlier designs. Load coincidence becomes increasingly unpredictable, particularly during evening EV charging, data-processing peak windows, or DG transition events. Systems designed primarily for apparent power and steady-state behaviour struggle under waveform distortion, and the safety margins assumed during design erode progressively during operation without obvious warning indicators.

Harmonic Distortion and the Thermal Reality It Creates

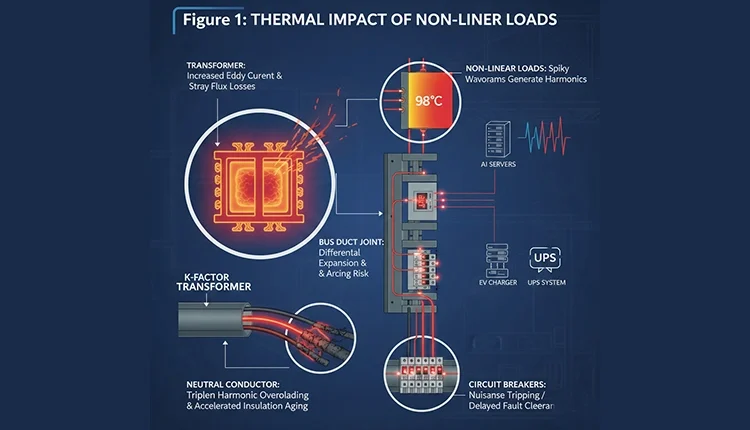

Harmonics are often discussed as a power-quality concern affecting efficiency or equipment performance. In practice, they represent a direct electrical safety risk. Harmonic currents increase I²R losses in conductors, transformers, and busbars, converting waveform distortion into sustained thermal stress.

In high-density buildings, third-order harmonics accumulate in neutral conductors instead of cancelling out, particularly in systems dominated by single-phase non-linear loads. This creates operating conditions where neutral currents exceed phase currents, a scenario rarely accounted for in legacy designs. Elevated neutral temperatures accelerate insulation degradation and increase fire risk, especially in concealed vertical risers.

Transformers experience additional core and winding losses under distorted currents. Eddy-current losses increase, stray-flux heating intensifies, and insulation life reduces even when kVA loading appears acceptable. These effects develop gradually and often remain undetected until irreversible damage has occurred. Capacitor banks and power-factor-correction systems may also interact with harmonic currents, sometimes creating resonance conditions that amplify distortion rather than mitigate it.

Vertical Distribution and the Hidden Heat Problem

High-rise buildings introduce a unique electrical vulnerability through vertical power distribution. Electrical risers, shafts, and bus ducts concentrate current-carrying conductors in confined spaces with limited ventilation. When harmonic-rich currents flow through bundled cables or enclosed bus ducts, heat dissipation becomes a dominant constraint.

Cable ampacity tables assume specific ambient temperatures, spacing, and grouping. In practice, riser temperatures often exceed these assumptions as electrical density increases over time. Additional circuits are added, loads grow, and original derating assumptions are silently violated. Vertical shafts become thermal traps where harmonic losses compound existing heat buildup.

Bus ducts are especially exposed. Their ratings assume balanced, sinusoidal currents and controlled ambient conditions. Under harmonic loading, busbars heat unevenly, joints experience differential expansion, and insulation stress increases. Repeated thermal cycling accelerates deterioration and loosening of joints, increasing the probability of arcing faults. Unlike cables, bus ducts often lack continuous temperature monitoring, allowing degradation to progress unnoticed until failure occurs.

Thermal failure in these systems is rarely dramatic at first. It manifests as gradual insulation breakdown, intermittent faults, unexplained heating, or nuisance alarms, frequently detected only when the system is already compromised.

Electric Vehicle Charging and Concentrated Risk Zones

EV charging infrastructure introduces a new class of electrical risk, particularly in basements and parking structures. Chargers draw high currents, often simultaneously, and exhibit strongly non-linear behaviour. DC leakage components challenge conventional earth-leakage protection, while pulsed loading patterns place stress on upstream transformers and feeders.

Basements already present unfavourable thermal conditions. Ventilation is limited, cable routing is constrained, and chargers are often installed close to combustible materials or vehicle fuel systems. When multiple chargers operate concurrently, localised heating becomes significant, especially where cable routes are long or poorly ventilated.

Earthing systems face additional stress as high-frequency components alter ground-impedance behaviour. Designs based purely on fifty-hertz assumptions may not adequately manage these currents, increasing touch-voltage risk during fault conditions. EV infrastructure is frequently added incrementally after building commissioning, without reassessing upstream systems, allowing risk to accumulate silently as charger density increases beyond original intent.

DG, UPS, and Grid Interaction as a Safety Event

Electrical safety is most often evaluated under steady-state operating conditions, where loads are stable and supply sources are assumed to behave predictably. In reality, some of the most critical safety vulnerabilities emerge during power transitions. When grid power fails, electrical systems are forced into a rapid sequence of events involving UPS systems, diesel generators, switchgear, and protection devices. The first few seconds following a failure define system stability and often determine whether downstream systems operate safely or drift into unstable conditions.

In buildings dominated by non-linear loads, DG–UPS interaction becomes particularly complex. UPS rectifiers impose sudden and distorted current demand on generators during recovery and recharge cycles. Diesel generators respond through their governors and automatic voltage regulators, which are often tuned assuming largely linear loading. The result can be voltage dips, frequency hunting, prolonged transients, or unstable recovery cycles that stress generators, cables, and connected equipment.

Harmonic content further complicates this interaction. During transfer events, harmonic levels can rise sharply, increasing thermal stress in generators and upstream distribution even before steady operation is established. Protection devices may respond unpredictably, leading to nuisance tripping, loss of selectivity, or delayed fault clearance. In some cases, sensitive digital loads shut down not due to faults but due to momentary instability outside their tolerance limits.

Most commissioning practices fail to test these conditions adequately. Acceptance testing typically verifies steady DG operation and basic UPS autonomy but rarely evaluates dynamic behaviour under realistic non-linear load profiles. Step-load tests, harmonic response assessment, and recovery performance under simultaneous load acceptance are often omitted. Systems that appear compliant during commissioning may therefore exhibit unsafe behaviour during real outages.

Protection Systems Under Non-Linear Stress

Protection systems form the final safety barrier in any electrical installation, yet they are among the most vulnerable components in environments dominated by non-linear loads. Circuit breakers, relays, and protective devices are calibrated assuming sinusoidal current waveforms and predictable thermal behaviour. When these assumptions no longer hold, protection performance becomes uncertain.

Under harmonic-rich conditions, thermal elements in breakers respond to elevated RMS current rather than true fault conditions. This can result in nuisance tripping under normal operation, particularly during peak harmonic loading. Conversely, magnetic elements may fail to respond appropriately to genuine overloads or short-duration faults when distorted waveforms affect sensing accuracy. The operating margin between nuisance tripping and delayed fault clearance becomes dangerously narrow.

Selectivity, a cornerstone of electrical safety in high-rise buildings, is particularly at risk. Harmonic distortion and transient currents during DG–UPS transitions can cause upstream breakers to trip before downstream devices, leading to widespread loss of supply instead of localised isolation. In critical buildings, such failures can disable life-safety systems, essential services, and digital infrastructure during emergency conditions.

Delayed fault clearance has severe consequences. Conductors and joints continue to heat under fault conditions, insulation deteriorates rapidly, and the probability of arc faults increases. These events often leave little visible evidence until catastrophic failure occurs. Protection coordination studies that ignore non-linear behaviour, waveform distortion, and transient operating conditions are therefore no longer sufficient. Protection engineering must evolve to reflect how modern electrical systems actually behave, not how they are assumed to behave under idealised conditions.

Earthing Beyond Fifty Hertz

Earthing systems form the foundation of electrical safety, yet they are among the least revisited elements as electrical loads evolve. Most earthing designs are based on fifty-hertz assumptions, where fault currents are predictable and ground-impedance behaviour is well understood. Modern loads challenge these assumptions directly.

Power-electronic equipment injects high-frequency and non-sinusoidal currents into grounding systems. At higher frequencies, impedance is influenced not only by resistance but also by inductive and capacitive effects, reducing the effectiveness of grounding paths designed for low-frequency faults. In practical terms, this can result in elevated touch voltages, unreliable operation of protective devices, and increased electromagnetic interference affecting sensitive equipment.

In EV charging environments, DC leakage components further compromise conventional residual-current devices, creating conditions where faults persist without effective disconnection. Earthing must therefore be treated as an active safety system rather than a static compliance measure. Design approaches should account for high-frequency behaviour, bonding continuity, and verification under real operating conditions.

Shifting from Capacity-Based to Behaviour-Based Engineering

The solution to emerging electrical risks does not lie in indiscriminate oversizing. It lies in understanding and engineering behaviour.

Design must begin with realistic load profiling and harmonic analysis. Neutral conductors should be sized based on expected harmonic currents rather than generic rules. Transformers should be selected with appropriate K-factor ratings where required. Cables and bus ducts must be derated based on actual thermal and harmonic conditions.

System architecture plays a critical role. Segregating harmonic-rich loads, zoning EV infrastructure, and isolating sensitive systems reduce interaction effects. Continuous monitoring through power-quality meters and thermal sensors provides visibility into conditions that would otherwise remain hidden. Protection settings must be reviewed with non-linear behaviour in mind, and coordination studies should account for distorted waveforms and transient events.

Commissioning and Lifecycle Validation

Commissioning must evolve alongside design. Load testing alone is insufficient. Harmonic measurements under real operating conditions, neutral-current verification, thermal imaging at peak load, and observation during power transitions are essential. Electrical systems are not static. AI deployments grow, EV adoption accelerates, and tenant equipment changes. Without periodic reassessment, systems drift away from their original safety margins. Lifecycle validation ensures that electrical safety keeps pace with operational reality rather than remaining fixed at the point of commissioning.

Conclusion: Electrical Safety Must Reflect Electrical Reality

India’s buildings are entering an era of unprecedented electrical density. Safety risks are no longer defined by nameplate capacity alone but by waveform distortion, cumulative thermal stress, and dynamic behaviour during power transitions. Electrical installations that appear compliant on paper may, in practice, operate dangerously close to their limits.

Ensuring safety in this environment requires a fundamental shift in engineering mindset. Capacity-based design must give way to behaviour-based engineering grounded in measurement, validation, and lifecycle oversight. Electrical systems must be evaluated for how they respond to distortion, heat accumulation, and transient events, not just how they are rated.

Equally important is recognising that electrical systems evolve continuously. AI loads expand, EV infrastructure grows, and operational patterns change. Without ongoing performance validation, safety margins erode quietly. When electrical systems are designed, commissioned, and maintained based on how they truly behave rather than how they are assumed to behave, buildings become safer, more resilient, and better prepared for modern technological demands.

Electrical risk has changed quietly. Engineering must respond with equal precision and intent.