Sound familiar? Not exactly the most positive form of communication, is it?

Be careful, pay attention, watch what you’re doing, follow the rules… and you won’t get hurt! Which may also be followed up with some non-verbal messaging intimating that, if you don’t follow the rules, we will fire you.

Unfortunately, when it comes to safety, most of us have not had a lot of positive communication. When you see the police in your rear-view mirror with the lights on, pulling you over do you say to yourself, “It’s OK, he probably wants to thank me for driving safely”? And most people do not find themselves overwhelmed with positive reinforcement at the workplace either. But the real problem with negative communication for safety is what it does or how it inhibits peer to peer intervention in “real time” out on the shop floor, in the field or at the “pointy end of the stick” as Sidney Dekker would say. As a result, almost all companies struggle to get their employees to speak up and say something when they see someone at-risk.

So, how can a workforce develop a common language for safety that isn’t so negative, and will make it easier for people to intervene? Well, for one thing, the common advice given at the beginning of this article: pay attention, watch what you’re doing, etc. will have to go.

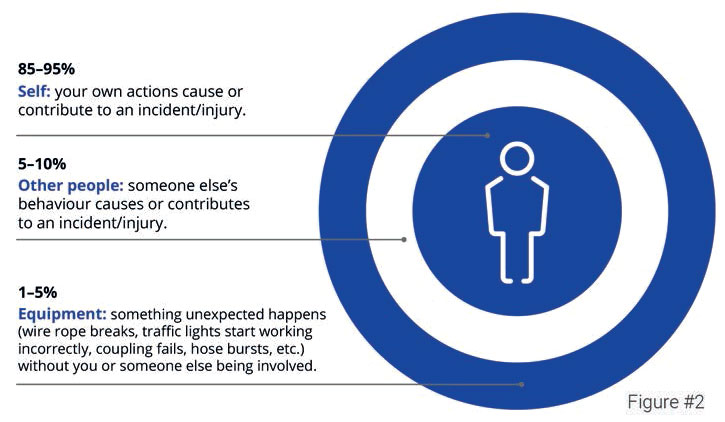

One of the reasons for this is that you probably heard those words repeatedly from your parents, who probably (most likely) loved you dearly, but chances are it wasn’t always in the nicest tone of voice. And if it came from your supervisor it might have been even worse. Eventually, even though it’s good advice, it becomes negative or it is received negatively. So, we will have to change the way people talk about inattention if we want them to intervene in real time. We could all speak up more often but the reason we don’t is that we know that the feedback or advice won’t likely improve our relationship. Most safety professionals know they can’t walk by someone standing on a chair to get something from a top shelf at work but rarely do they “bother” to correct their spouse or partner if they see them doing the same thing in the kitchen. But just changing the vernacular alone isn’t going to be enough. Employees and supervisors have to know what causes inattention or what causes someone not to have their eyes on task and their mind on task. Furthermore, they have to understand that human error, specifically their error not someone else’s is involved in over 95% of all the accidental injuries they have experienced. (See figure #2)

This is a big paradigm shift for most employees. Most employees still think workplace injuries are caused by the hazards, instead of realizing that there are hazards everywhere and that we negotiate hundreds or thousands of hazards every week (or in some cases every day if you drive in a big city) with our eyes and minds alone. Sure, our hands are moving the steering wheel and our feet are hitting the brake but that only happens if we see the red light or the transport truck in the first place. But unfortunately, the overwhelming focus on workplace hazards has persuaded many workers to believe that it’s all about the hazards and potentially unsafe equipment.

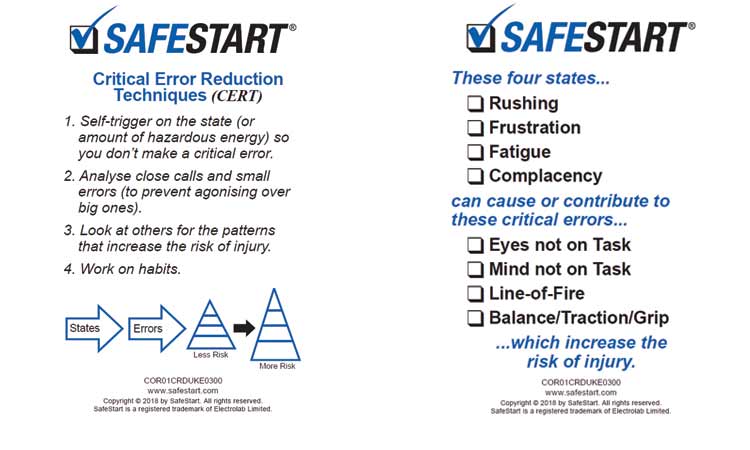

However, once your employees know that these four critical errors: eyes not on task, mind not on task, moving into or being in the line-of-fire and losing balance, traction, grip are involved or are contributing factors in over 95% of their injuries they begin to appreciate the importance of inattention. Unfortunately, that still isn’t going to be enough. In order for the communication to be positive it also has to be practical. And becoming complacent with workplace hazards that don’t change much is just the way our brains are hardwired. So, telling people to pay attention at all times really isn’t possible once the fear or skill is no longer preoccupying. (See figure #1).

So, we also have to teach everyone what causes inattention. Once again, over 95% of the time it will only be four states: rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency or a combination of them. Now, not only do they know how important inattention is when it comes to accidental injury causation, they also know what causes it. So, we can say, “Hey, you look pretty tired. Make sure to keep your mind on task?” Or if you saw someone going too fast or a lot faster than what’s normal for them you can say, “on a scale of 1-10 how rushed are you right now?”

Asking them to “rate your state” is much more friendly than saying “don’t rush” which will probably just increase their level of frustration if they are already behind on a job or running late. It also forces their mind to use their pre-frontal cortex instead of their lizard brain – which is usually all we’ve got working for us when we are in a rush. Similarly, telling someone to “calm down” when they’re angry will likely just make them angrier. Whereas asking them to rate their state lets them see (for themselves) that their level of frustration is at a dangerous level.

When we first started implementing SafeStart 20 years ago some of the workplaces and companies we got to work with like the railroads in Canada had very negative safety cultures. Although there was a lot of initial resistance when the training started it didn’t take very long before the workers were saying, “hey, eyes on task” and then they’d point to a car rolling towards them. Or, “hey, line-of-fire”, and then get them to look at the fork truck that was loading the box car.

In short, it gave them a way to communicate that was effective and wasn’t perceived as negative by their co-workers. Furthermore, the employees started freely volunteering the states and errors when an incident happened or they experienced an accidental injury. Instead of trying to diminish or deflect, they were analysing what was really happening and learning how to improve or prevent the next one. 1200 people went 9 months without so much as a first aid injury and a lot of credit, according to their union representative was due to having a new vocabulary that people had incorporated into their lexicon. (See figure #3)

Since then, thousands of workplaces have benefited from having a new way to communicate the risk of inattention without causing frustration or damaging their relationship. Intervening became close to risk free because it was friendly and almost always well received (most people would say thanks when someone pointed out a line-of-fire hazard or something that could cause a loss of balance, traction or grip. Yes, there is some training involved. Creating a positive safety culture isn’t going to be effortless. But it’s a lot quicker and a lot more reliable than hoping that the “messaging” from senior management actually reaches the shop floor. They can tell everyone not to walk by an unsafe act without saying anything but at most workplaces that message was largely ignored.

If you give people the right perspective to work from and a new vocabulary to work with that makes sense to them, they will intervene and they will do it in real time or as soon as they see someone at-risk. And isn’t that really the culture we allwa nt, where everybody in the workplace actually does look out for each other?